Essay

Preface

Rural Utopias brings together the work of ten artists who participated in a series of residencies in remote and regional Western Australia from 2019-2023. In collaboration with their host communities, artists developed context-responsive and socially engaged projects responding to the theme of Rural Utopias.

-

Rural Utopias, 2023, The Art Gallery of Western Australia. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

Rural and remote locations have historically attracted visionaries and dreamers in pursuit of utopian goals, including alternative lifestyle or spiritual communities and economic development projects. These ventures are often cast as alternatives to the dystopian urban lifestyle, typically seen as detached from nature and deprived of community bonds. In colonial nation states such as Australia, this notion of utopia is challenged by the realities of a society living on unceded First Nations territory and the absolute necessity of recognising their continuing connection to Country and generations of storytelling.

Artists developed their projects in consultation with communities to respond to, challenge or question the idea of ‘rural utopias’. The projects take many different approaches to the question of what utopia might look like, mean or feel like in Australia within the context of a regional or remote community. Each project needed to respond to the specificity of each location — its unique stories, landscape and perspectives.

These community activities and reflections on utopia are as broad as a community harvest ball, a peer-to-peer knowledge sharing weekend, collaborations with community choirs, working in a skimpy bar or volunteering at a radio station, to name just a few of the activities undertaken during the residencies.

-

George Addis, Brooch, c1900 18-carat gold, The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, Purchased through The Art Gallery of Western Australia Foundation and Linton Currie Trust, 2018, Georgie Mattingley, Golden Utopia (Main Reef Tavern I), 2022, digital photograph. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

Rather than being limited by the theme or a search for utopia, each project encompasses some of the passions, priorities and experiences of people living in regional and remote communities who can guide and shape the artist’s experience of their residency as well as the artistic outcome. A network of community organisations from each location generously host the artist, facilitate introductions and connections with community members and present workshops, exhibitions, and other activities presented by the artist throughout the course of the residency. This process allows relationships and connections to unfold over time, inviting a considered and reflective response to the idea of utopia within each local context.

-

Jo Darbyshire, Lake Grace, 2022, oil on canvas, Andrea Williams, Mummaries 1-5, 2023, wire and mixed media. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

Common narratives or themes arise across the projects, creating links between places and people across Western Australia. These include environmental destruction brought about by farming, extractive or development projects, the importance of First Nations cultures including stories of survival and displacement, mining and resources as a source of both wealth and destruction, practices of giving and sharing, and the importance of making spaces for community activity.

Working in collaboration with The Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA), the exhibition is accompanied by artist-selected works from the State Art Collection. The invitation from AGWA for artists to consider this collective hoard of cultural wealth was both an exciting and daunting challenge — with a collection of over 18,000 works of art, where should one begin to look? In a state as large and sparsely populated as WA, what relevance does a collection housed in a gallery in Perth hold for the people of Kununurra, Carnamah, Esperance or Roebourne? What stories are held within the collection that might resonate or sit alongside the stories learned through conversation, workshops and time spent with local communities?

These questions arose in different ways through discussion with each artist during their project, and conversations about the collection and its role in the cultural life of regional communities shaped many of the residency projects. The process of sifting through the collection to find points of connection, synergy or a spark of interest is in many ways similar to the approach taken by the artists in learning the stories and forming relationships in the community, and the challenge of distilling the multitudes of experiences of their residencies into a final outcome can be as daunting as finding the perfect artwork from the vast collection to sit alongside it.

Some artists chose to use collection works to geographically locate or visually represent their works, to present a cohesive narrative across their installation or add emphasis to the focus of their project. Alana Hunt’s choice to include Elizabeth Durack’s landscape illustrations of the East Kimberley provides a historical punch to Hunt’s portrayal of the ongoing violence of colonial developments and the destruction of Aboriginal sacred sites, legalised through bureaucratic means, while Georgie Mattingley’s inclusion of a Gold Rush-era brooch, intricately decorated and designed in art deco style, is a visual representation of the excesses — and inequalities — of both past and present Kalgoorlie.

-

Louis Buvelot, Landscape, 1882, oil on canvas.The State Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia, purchased 1970. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au) -

Elizabeth Pedler & Josten Myburgh, What is written upon a leaf, what is held within a seed, 2023, mixed media installation, Sydney Parkinson, Baeckea imbricata (Banksian name: Philadelphus imbricaus) (from Banks' Florilegium Parts V & VI), 1772–1784, colour engraving on paper, The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, purchased 1982, Darwinia fascicularis (from Banks' Florilegium Parts V & VI), 1772–1784, colour engraving on paper, The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, purchased 1982, Utricularia Caerulea (from Banks' Florilegium Parts XI & XII), 1772–1784, colour engraving on paper, The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australa, purchased 1983. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

While some artists worked with the collection to add weight and context to their own works, others used the chosen work as contrast or counterpoint to their experience. Bennett Miller’s inclusion of Landscape (1882), the work of Louis Buvelot, a 19th century Swiss artist from Victoria, speaks to the ‘wrongness’ of European approaches to representing Australian landscapes, as well as the destruction of the landscape over time as a result of ongoing environmental destruction. Elizabeth Pedler’s installation departs from the detailed copperplate engravings of plant specimens collected by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander to celebrate the messy entangling of lives, both human and non-human, that sit alongside each other and are less easily categorised and documented.

-

Nathan Gray, The Marlaangu Project, 2023, audio, Wendy Hubert, Cave at Kumina, 2021, synthetic polymer paint on paper, The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, Purchased through The Art Gallery of Western Australia Foundation: TomorrowFund, 2022. © Wendy Hubert / Copyright Agency, 2021. Wendy Hubert, Thalarut Pool, Pannawonica, 2021, synthetic polymer paint on paper, The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, Purchased through The Art Gallery of Western Australia Foundation: TomorrowFund, 2022. © Wendy Hubert / Copyright Agency, 2021. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

Other artists found personal and family connections within the collection. Nathan Gray’s recorded stories of Yindjibarndi ghost tales is accompanied by the rich visuals of two works by Wendy Hubert, a Yindjibarndi artist working with Juluwarlu Aboriginal Corporation who supported Gray during his residency. Jo Darbyshire and collaborator Andrea Williams were moved and excited to find two works from Andrea’s uncle Ronald ‘Womber’ Williams painted in 2011, the last year of his life. These deeply personal and familial connections are testament to the living nature of collections and the role they play in forming and sustaining connections between artists, those living and those who have passed, and telling stories of families, cultures and practices that can be passed onto future generations of artists.

-

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Rowan, 1987, card, Blue/Lark, 1983, card, Willow, 1987, card. The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, Gift of Mary Hill in memory of Christopher Hill, 2021, © Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au) -

Sarah Rodigari, Biosphere, 2023, single channel digital video with sound, 18 min 33 sec. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

Both Sarah Rodigari and Jacky Cheng approached the collection by finding resonances in artistic practice, selecting artists with similar approaches or interests. Rodigari’s discovery of a collection of works by Ian Hamilton Finlay, a Scottish poet, chimed with her approach to making work by collaging text, image and sound, inviting audiences to take the time — and make the effort — to engage with the work. Jacky Cheng’s materially-focused practice draws our attention to the creases, cracks and patterns in old buildings, and their transformation over time as their materials are reclaimed and reused. Jane Whiteley’s collection work Sides to the Middle (1992) does the same with fabric, reminding us of the imprints and creases left by bodies upon everyday materials, the visual remnants of living.

-

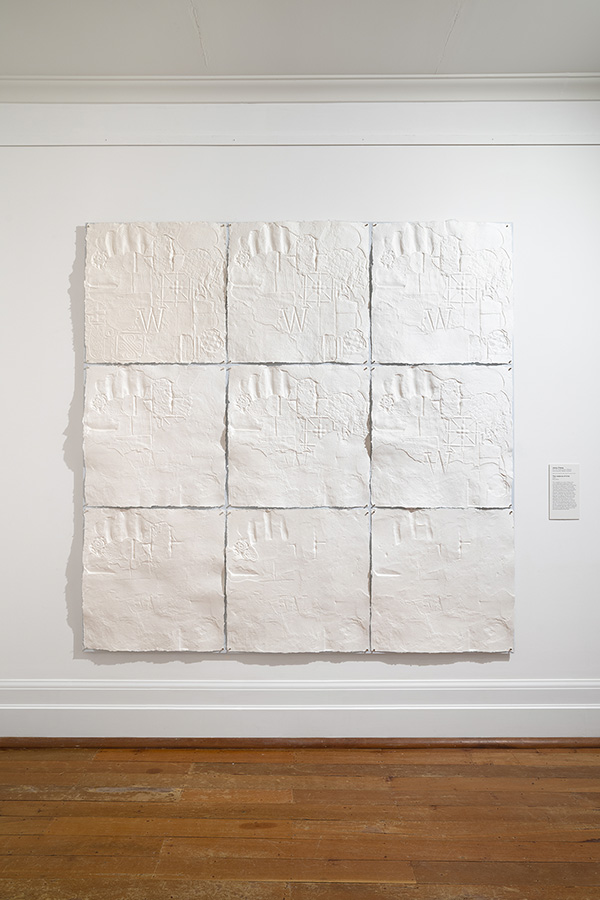

Jacky Cheng, The cadence of time, 2023, kozo fibres. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

The invitation to ‘respond to the collection’ is conceptually challenged by artists Ana Tiquia and Tina Stefanou. Both artists consider the contradictions of a collection based in Perth for the people of WA, but the forms each work take diverge from there. Tiquia’s work takes the collection outside the gallery walls, invoking the practices of giving and sharing she witnessed in Esperance to reimagine a different way in which the State Art Collection can be enjoyed, shared and even interacted with, through increased digitisation and peer-to-peer networking. Stefanou’s work breaches the collection stores, bringing the work inside to perform alongside the quiet — and secure — spaces where artworks rest and are restored. She takes footage from her time in Carnamah — shearing sheep, performing with the community, and presenting the first harvest ball in over a hundred years — within the walls of the gallery, to give equal weight to ephemeral and organic (in more than one sense) activities and practices. In doing so, she reminds us of the importance of preservation, both of community activity and of the environment and resources that support and sustain us.

-

Tina Stefanou, Back-Breeding, 2023, sculpture, wool, seeds, feathers, sweat, sheep body, muscle, 3,500 kilometres of thread, seed-stitching. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

At the core of SPACED’s residency programs over the past 25 years has been the challenge to artists to consider perspectives, contexts and viewpoints other than their own, which can sometimes be unfamiliar, conflicting or perplexing. Rural Utopias extends this challenge to artists to also locate their work alongside those of other artistic practices expanding across time, media and culture.

-

Ana Tiquia, Seeder Futures, 2023, shared folder; P2P file synchronisation, application built on BitTorrent protocol, high-resolution .jpg files of public domain, artwork from AGWA’s collection; digital, videos with sound, Georgie Mattingley, Super Pit Curtain (Boulder Camp), 2022, digital print on vinyl banner. The Art Gallery of Western Australia, 2023. Photo by Dan McCabe (@artdoc_au)

Capturing the richness of socially engaged residency experiences across the state and the relationships formed and sustained is as challenging as capturing the richness of the collective cultural wealth of the State Art Collection. The process of placing the works of the artists selected for Rural Utopias alongside their choices from AGWA’s collection invites the creation of exciting new connections while celebrating the depth of community experiences, stories and arts practices that continue to flourish across the state.